It’s nearly impossible to adequately discuss Jim Karn’s career—and his legendary status within the climbing industry at-large—without referencing the current American scene. Nowadays, Nathaniel Coleman is a superstar, in large part because of the four times he won the national bouldering championships. Prior to Coleman’s competition ascendancy, Daniel Woods ruled the men’s division with consistent championships wins as well. Beyond the competition scene, there are big names such as Jimmy Webb, who has complemented his climbing success by shaping popular lines of holds. Alex Puccio did something similar with her line of Puccio Pinches.

There’s practically an idealized template now—in 2021—for being a successful professional climber, which begins with competition supremacy at the national level (no small feat) and morphs into hold shaping and international success, all underscored by renown and acclaim for various climbing outlets, of course. But someone had to establish that model, and prove that it could be a viable pathway.

In large part, the contemporary template was fashioned by Jim Karn. He was practically unbeatable on the nascent American competition scene in the late 1980s and early 1990s. He parlayed that success into World Cup accomplishments at a time when very few Americans were traveling abroad to compete. And, perhaps most importantly for the industry, he helped usher in an entire new era of handholds that allowed hold shaping and hold marketing to evolve throughout the 1990s.

An athletic pedigree

Considering that Jim Karn would eventually help establish a unique standard of climbing professionalism, it’s fitting that his interest in climbing began somewhat uniquely as well. At a time when climbing, on the whole, attracted a lot of social outcasts and rebellious vagabonds, Karn—as a child in the 1970s—was the anomaly. He was voraciously interested in sports, and the fact that he grew up in Ohio adds another unique element to his story and distances him from the mountainous childhood milieu.

“I also read a lot, so I kind of just worked my way through all the sports-related books at the local library,” Karn recalls of his childhood and his interest in sports. “The library actually had some really good climbing books that got me interested in the sport. So, I went out and found these dried-up waterfalls—little crags of junk limestone, and started climbing on those, teaching myself. Eventually, I found this legitimate climbing area called Clifton Gorge, so I went out there and met some real climbers. It was just kind of a top-rope area, but it was actually really high-quality limestone. More importantly, the locals were fantastic people who took care of me and taught me a lot.”

As Karn’s knowledge of climbing increased, so did his desire to leave Ohio. Climbing gyms did not exist in the United States at the time, so Karn longed to head west for more climbing access. He graduated from high school a semester early, hopped in his car, and eventually wound up selling shoes at an REI store in Denver. He saved whatever money he could, which allowed him to venture farther west—to Joshua Tree. “That was the start of a few years of living in a tent or on someone’s couch full-time and just catching rides from one climbing area to the next, stopping occasionally to work some odd job for a few weeks or months until I had enough money to hit the road again.”

Karn might have been living a low-key, peripatetic existence, but people would soon come to know his name on the elite-level competitive scene. In fact, from the summer of 1989 to the spring of 1990, Karn won every major competition on American soil—including a pair of Rockmaster competitions organized by famed ice climber Jeff Lowe in Seattle and Berkeley. Karn also won a North American Continental Championship, which was the precursor to contemporary events such as the Pan-American Championships or the forthcoming North American Cup Series. And Karn was the highest-placing American man at the 1990 World Cup competition in Berkeley, the most prestigious competition ever held in the United States up to that point.

The competition scene in late-1989 and early-1990 appealed to Karn for a couple reasons. First, it dovetailed perfectly with his childhood interest in sports and his longtime desire to be an athlete; Karn’s rise in the competitive ranks was not that of a dirtbag climber dabbling in an occasional contest, but that of a highly trained sportsman plying his athletic trade, a fairly novel concept at the time. He trained for competitions and he strategized accordingly.

Secondly, competitions stripped climbing to its core, in Karn’s opinion, and left little room for doubt or deception. “At that point in time, that was sort of the beginning of the concept of a professional climber, somebody that could make enough money to not have a job, just climb full-time,” he explains. “As a result, some people were not completely honest about their accomplishments, which I found quite frustrating. The nice thing about competitions was it was there for everyone to see—you couldn’t exaggerate your results.”

Going global

As Karn won more competitions, he acquired more prize money and caught the attention of would-be sponsors. But there were sacrifices, as it was a slow process in an industry that was only starting to emerge. “A lot of those early events—I basically would go to the event completely broke, and if I didn’t win prize money, I was looking for a job the next day,” he recalls.

However, with greater success came a greater realization that Europe—rather than the United States—was the place for a top-level competition climber to be. At the time, European countries like France and Italy had more contests, they hosted more World Cup events, and they featured a more robust climbing industry all-around. So, in the early 1990s, Karn adopted a routine: He would save a couple thousand dollars, just enough to purchase a one-way-ticket to Europe. He would then stay in Europe as long as he could, just until the money was about to run out, and fly back to the United States to start the process all over again.

While engaged in this routine, Karn realized just how far behind the American competition scene was. For instance, Karn often had to sleep in a tent throughout a given World Cup weekend, while competitors from other national teams slept in hotel rooms and had their travel expenses paid by their respective federations. Regardless of the discrepancies, it was typically a friendly scene, with Karn often training with competitors from other countries, learning mostly from the French elite. In the process, camaraderie developed. “I remember one World Cup in Italy, where the French B team realized I was sleeping in a tent, so they invited me to sleep on the floor of their hotel suite,” he says.

Karn’s competition accomplishments in Europe were many, most notably becoming the first North American to win a World Cup lead competition—held in La Riba, Spain—and maintaining high placements in the circuit’s annual overall rankings for several years. As a result, Karn, and other Americans such as Lynn Hill and Robyn Erbesfield, played critical roles in proving to the rest of the world that American climbers were just as elite as those of the leading European nations.

Advancing the industry

Karn’s competition success allowed the burgeoning American climbing industry to have a star, someone around which ideas and products could crystalize. Nowhere was this more evident than with climbing holds. A California-based company called Climb It eventually approached Karn sensing an opportunity. Other sports were blending star athletes with sport-specific merchandise—Michael Jordan with Nike’s Air Jordan shoes, most prominently—so it made sense that the climbing industry could adopt a similar model.

The outcome of Climb It’s correspondence with Karn was the idea that Karn himself could shape a full line of holds, eventually called the Monster Holds. “[Climb It] just asked if I wanted to do it,” Karn remembers. “They mailed me some blocks of foam, and I just started hacking some holds out. At that time, it seemed like most holds were sharper and more painful than they needed to be. I realized that plastic holds did a bad job of recreating real rock, so I didn’t try. I focused on ergonomics and comfort in those early shapes.”

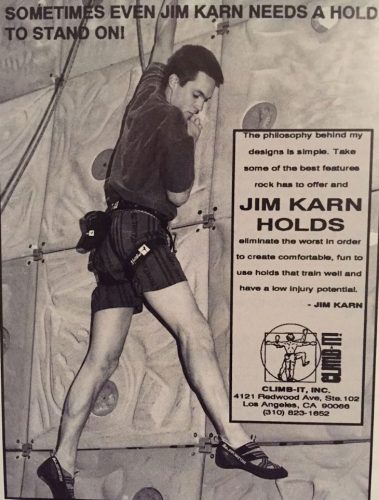

Karn’s holds were revolutionary. Created to be smooth and comfortable, they varied in size from small footholds to larger macros. Most importantly, they did not try to mimic natural shapes—they were unabashedly the unique creations conjured up by Karn. “The philosophy behind my designs is simple,” Karn stated in one advertisement for the Monster Holds. “Take some of the best features rock has to offer and eliminate the worst in order to create comfortable, fun-to-use holds that train well and have a low injury potential.”

The climbing world soon caught on to the visionary idea, particularly as climbing gyms started appearing in cities around the country. “No gym will be complete without a pair of these babies,” wrote one magazine review of the holds in the 1990s. “The texture is smooth and can be used for long, heinous workouts. These Climb It holds also tighten down really well without breaking or rotating. They are affordable and fairly lightweight, which cuts down on shipping cost. Don’t miss out on these.”

Karn’s competition career wound down in the mid-1990s. Around the same time, Climb It retired the Monster Holds line, but not before other brands started realizing the necessity of producing uniquely rounded and comfy shapes—or utilizing climbers’ fame for greater merchandising potential. Karn stayed in the climbing industry, eventually taking a job with one of his earliest sponsors Metolius—where he still works as a product designer.

Whether gauged as an eminent figure in the early days of the American competition scene, a pioneer for helping to push hold design beyond its faux-stone roots, or an inspiration for an entire generation of young fans who would eventually join the industry as gym owners, coaches, and routesetters, Karn deserves a lot of the credit. It would be a different scene and a different industry nowadays without Karn’s contributions.